January 22, 2019 | 7 minute read

Toyota started a revolution in factory work with the Toyota Production System, commonly called “lean thinking”[i]. Since the 1990’s it has dominated the manufacturing floor with good reason—this mindset increases customer satisfaction, improves organization financial performance, and builds worker engagement. Many of the Toyota techniques from decades ago[ii]—Value Stream Mapping, Kaizens, and the 5 Whys—still translate directly to factories of every stripe. Because it works so well on the factory floor, it’s natural to wonder if lean thinking translates to “Knowledge Work.”

Figure 1. Knowledge Work is done by those who “think for living”

Knowledge Work[iii] is done by those who “think for a living”, for example, doctors, engineers, business developers, and entrepreneurs (see Fig. 1). Certainly, some companies such as Danaher Corporation have shown great success applying broad principles of lean to knowledge work. But they rely on decades of broad expertise in lean manufacturing. How do we present lean knowledge work in a more accessible way, a way that doesn’t require deep manufacturing experience? The answer lies in grasping lean concepts at a fundamental level. To that end, here are five lean-knowledge principles you can use even if you’ve never stepped on a factory floor:

Principle 1. Value is what the customer is willing to pay for.

Each day knowledge staffers expend a lot of effort. Unfortunately, just working hard doesn’t create value. In fact, only a portion of our effort does that. We will define value as “something a customer is willing to pay for.” Maybe it’s a brilliant solution to a customer’s problem or perhaps it’s something less exciting but just as necessary, like documenting that solution.

Value comprises all the things necessary to satisfy important customer needs. But exactly who is the customer? For knowledge work, it can be complicated: it may be a consumer, another business, or, as is common in knowledge work, another person in your org. To identify the customer, first identify who decides 1) the work is needed and 2) when it’s “done.” That’s probably your customer.

Principle 2. Waste = Effort – Value

If value is what a customer will pay for, waste is all the effort we expend that doesn’t create value (see Fig. 2): every time we fix a mistake, create something customers don’t really want, or spend time planning something we never get to. How much of our effort is waste? The magnitude may surprise you. The most common estimates of waste are around 85%! 15 years ago, when I first heard that number, I thought “not us…we’re better than that.” Today, I believe it. (Sometimes I wonder if 85% is a little low!)

Figure 2. Waste is the difference between how hard we try and the value we create.

Incidentally, common sense is not so common and is the highest praise we give to a chain of logical conclusions. Eli Goldratt

Principle 3. Common Sense Solutions: The 3 Levers

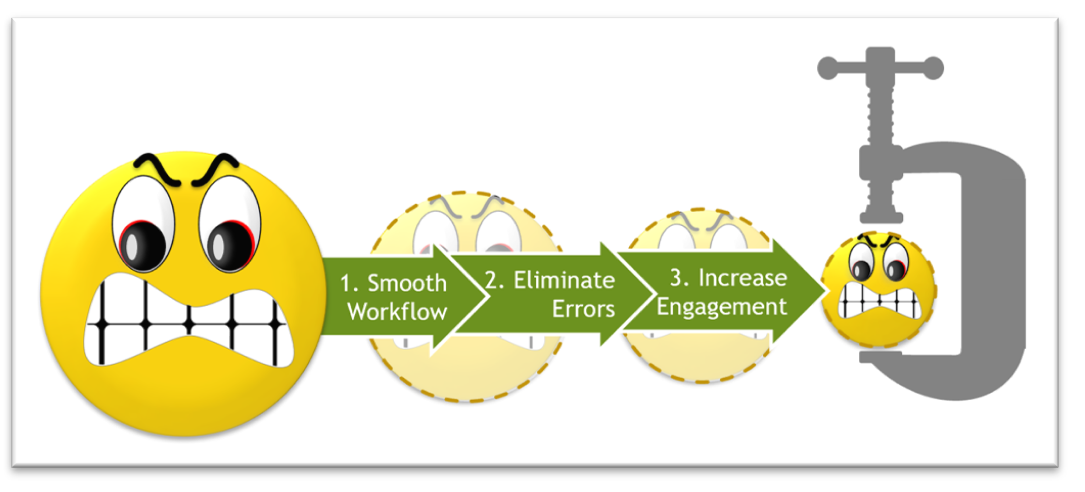

So much writing on lean thinking is a stream of consciousness—countless anecdotes without foundation. Anecdotes are interesting, but you can’t apply them to a new situation and in knowledge work every situation is new! Lean knowledge must be understood at a more basic level. Although waste is expressed in endless varieties, it can be addressed with just a few common-sense principles we’ll call the “three levers” (see Fig 3):

a. Simplify the workflow—break complex workflow down to simpler steps, make the flow more visual, and create “playbooks” for the team to react to the unforeseen. Clarity of what we’re doing and how we are doing it will slash waste every time.

b. Eliminate errors—doing it twice is pure waste. So is all the explaining—to the boss and the customer—about what happened and why it won’t happen again. Solutions like clear standard work, peer review, and error proofing can slash error count.

c. Engage knowledge staff—knowledge work has a unique dependence on the people who do the work. You want them engaged like sports fans: sharing the organization’s goals, protecting the brand, and playing to win. Okay, maybe they won’t cheer at team meetings. But engaged knowledge staffers will outperform their bored, disgruntled counterparts by a wide margin.

Figure 3. The Three Levers: Common-sense ways to slash waste in knowledge work

An example:

Consider an example of the three levers: a team of 4 or 5 professionals are perpetually oversubscribed. This could be engineers, marketers or accountants. Let’s say the organization’s normal practices conspire to continuously demand from them 130% of what they can do. A few months of this and customers are angry because work is always late; this throttles revenue, which disappoints a lot of people. And even with all the work to do, team members don’t seem to be trying as hard as they used to. How can we address this?

A common cause for this situation is a broken prioritization method, one that cannot distinguish a must-have from a nice-to-have. A broken prioritization system continuously takes on too much work. This creates a sort of traffic jam. The result is sprawling backlogs that bloat wait times and demand endless status updates for stuck work. This clogged highway has waste overflowing.

Prioritzation problems can addressed with the three levers:

· simplifying the prioritization process to focus the available capacity on the most important things while being clear about what we are not doing,

· eliminating errors by reducing the stress of systemic oversubscription and multitasking, and

· creating satisfaction for the team by freeing them from a “contest that cannot be won.”

The best tool here is often the Kanban Board, created by David Anderson[iv]. I’ve watched Kanban boards cut large swaths of waste, which leads to increased productivity and improved customer satisfaction, all while rocketing engagement. This thinking can be applied to many other areas such as improving design quality, deepening understanding of customer needs, and increasing intellectual property.

Principle 4. Improving Knowledge Work Increases Measurable Value

This principle may be the most important to the boss. Lean knowledge isn’t a fad or a nice way to talk with colleagues. The hard edge of knowledge work is it’s there to support a business, and business performance can be measured. Techniques that don’t create real value don’t last. As shown in Fig. 4, knowledge work creates value in five ways that never get old: Increase revenue, reduce cost, speed up delivery, reduce quality defects, and increase compliance/protection (including intellectual property).

Figure 4. In knowledge work, value can be quantified in five categories

A relentless barrage of “why’s” is the best way to prepare your mind to pierce the clouded veil of thinking caused by the status quo. Use it often.

Shiego Shingo

Principle 5 See it broken. Watch it work.

We all have some amount of “solution blindness:”—once we think we know the answer, we too easily stop searching. But a large amount—perhaps 30%[v]—of what we think is wrong[vi]. Not dead wrong, but wrong enough and wrong in ways we can’t imagine. Only through deep understanding of what’s not working can we improve. So, see it broken yourself—never be satisfied looking through the filter of another person. Use the product. Talk to the customers. Listen to the knowledge staff. And just as important, watch it work after a solution is put in place. Understand what behavior is changing because real improvement always changes behavior.Perhaps these five principles will help you as you seek opportunities to improve your organization. They guide me daily. There are no formulas to success, no check-the-box thinking, no shortcuts to diligence and competence. It’s all hard work but incredibly satisfying to watch an organization create more value while the company experts expand their expertise and increase their job satisfaction.

About the author: George Ellis practices and writes about lean knowledge work. He retired from Danaher after 35 years of service, most recently as VP Global R&D for X-Rite. He now develops lean knowledge work tools and is writing “The Knowledge to Improve” to be published later this year by Elsevier Press.

References:

[i] Womack, James P., Daniel, T. Jones (1996) Lean Thinking

[ii] Womack, James P., Daniel T. Jones, Daniel Roos (1990) The Machine That Changed The World

[iii] Drucker, P. F. (1959). The Landmarks of Tomorrow New York: Harper and Row.

[iv] Anderson, David – Deep Kanban. Worth the Investment? Lean-Kanban University. 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JgMOhitbD7M

[v] Taiichi Ohnos Workplace Management: Special 100th Birthday Edition – Taiichi Ohno (2012)

https://publicism.info/business/workplace/2.html

[vi] The number “30%” is borrowed from Taiichi Ohno, the father of lean thinking and the creator of the Toyota Production System. He said “A thief may say good things three times out of ten; a regular person may get five things right and five things wrong. Even a wise man probably is right seven times out of ten, but must be wrong three times out of ten, so if you are wrong don’t hesitate to correct yourself.”

Author

GEORGE ELLIS

Vice President, Innovation Practice

Meet George

GET MORE INSIGHTS

Subscribe to our newsletter, Lean Focus Forward, for the latest industry insights, upcoming webinars, and more.